Shooting for the Moon

Before rockets, before NASA, before the space race was even a glimmer in anyone’s eye, Jules Verne had an idea: what if you just built a really big gun and shot people at the Moon?

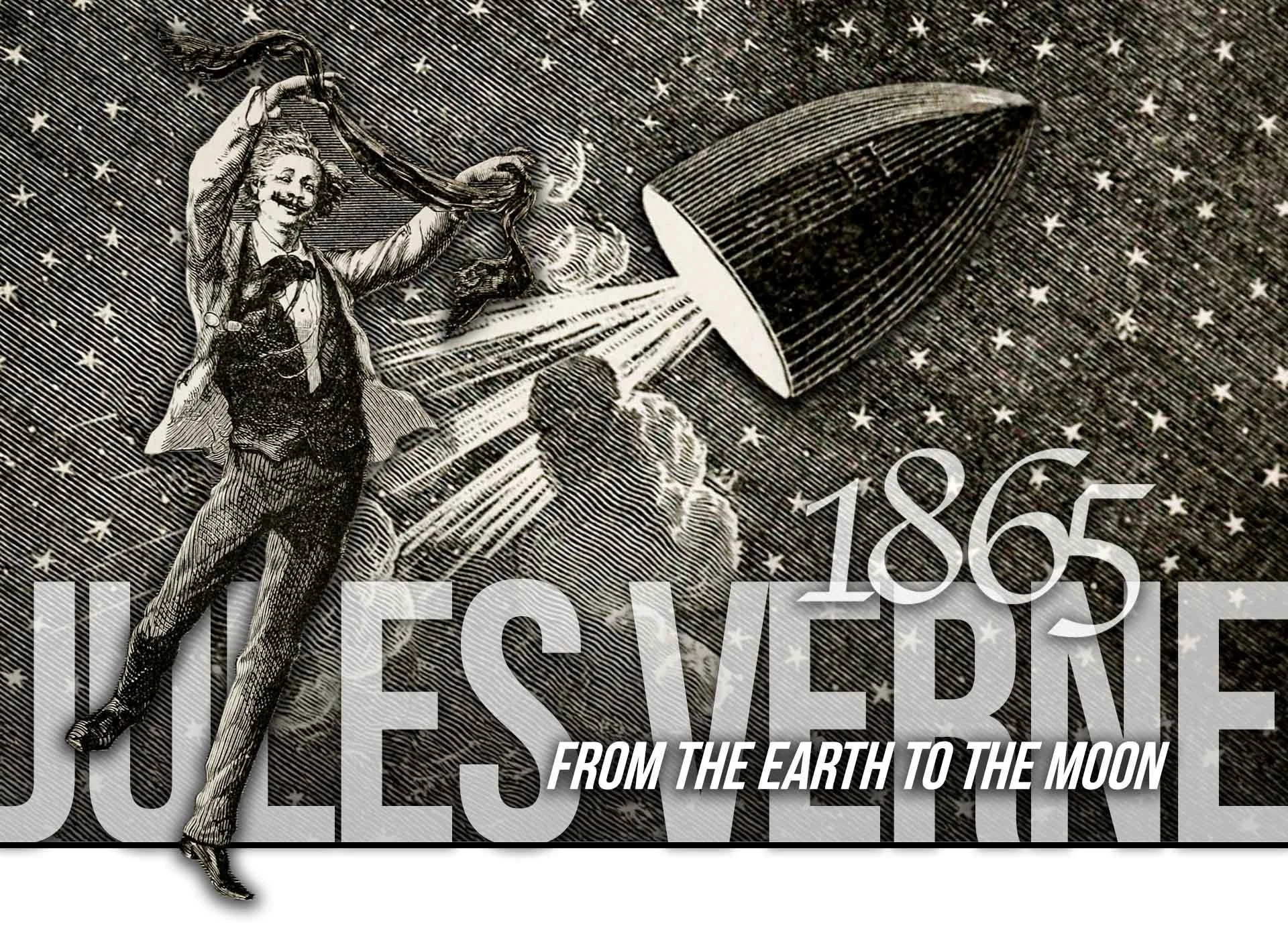

That’s the premise of From the Earth to the Moon (1865)—one of the earliest pieces of science fiction, written when “space travel” was barely a phrase. Part satire, part science dream, it’s a story that reveals as much about 19th-century America as it does about our endless urge to go up there and see what’s out there.

Even if the science is hilariously wrong (spoiler: cannons = instant death), the audacity of the idea still hits. It’s a book worth knowing, especially for younger sci-fi fans who want to see where the genre first started flexing its big imagination muscles.

-

Jules Verne’s 1865 book was an early sci-fi classic about a trip to the Moon.

Instead of rockets, the plan was to launch people out of a giant cannon.

It reflects post-Civil War optimism and obsession with engineering.

The book inspired later writers (and NASA engineers!) even though the science was bonkers.

It’s full of humor, absurdity, and surprisingly modern “fan club” energy.

The Big Gun That Started It All

Imagine This

It’s the 1860s. America has just finished a brutal Civil War. Everyone is broke, traumatized… and bored. Then a group of gung-ho artillery enthusiasts decides the best way to lift everyone’s spirits is to build the world’s largest cannon and shoot a bullet to the Moon.

Honestly? Same vibes as your buddy who insists he can build a flamethrower in his backyard.

Verne’s Baltimore Gun Club, the stars of the story, were obsessed with bigger, louder, faster. Their solution to space travel wasn’t subtle. Rockets? Too fancy. Just load up a massive cannon, climb inside, and boom—you’re lunar history.

Once upon a time, our best plan for reaching the Moon was to get drunk, build a cannon, and fire ourselves into space. That’s sci-fi history. And it’s kind of glorious.

The Science

Here’s the thing: a cannon blast would liquefy you before you ever said “Lift-off!” But in 1865, this all made sense. Physics hadn’t yet been the ultimate party pooper.

Airbags? Nope.

Heat shielding? Nah.

Acceleration G-forces? Sounds fun!

Realistic? No.

Entertaining? Oh, 100%

Verne tried to calculate the speed and size needed (props to him for even attempting math). The result was less science, more “let’s just see what happens.”

“I don’t know if there are inhabitants on other worlds—

so I’m going to see!”

What’s Cool About It

First contact with sci-fi ambition

This was one of the first books to seriously ask, “Could we leave Earth?”Historical snapshot

It’s like a time capsule of 1860s America: post-war pride, engineering mania, and an early form of crowd-funding to make it all happen.Fandom before fandom

The Gun Club is basically the world’s first fan club. Replace cannons with cosplaying and conventions and you get the idea.

In 1865, physics had not yet learned to ruin the fun.

Why Modern Sci-Fi Fans Should Care

If you love sci-fi today, Verne is like your genre’s great-grandparent. His wild ideas opened doors. Reading From the Earth to the Moon is like seeing ground zero of the imagination explosion. It makes you appreciate how far we’ve come (and how much we still love ridiculous ideas).

Also, it’s short. You could finish it in an afternoon and spend the evening arguing on Reddit about whether cannon travel deserves a comeback.

So next time you see a launch on TV or watch a Hollywood blockbuster about brave astronauts, remember: once upon a time, our best plan for reaching the Moon was to get drunk, build a cannon, and fire ourselves into space. That’s sci-fi history. And it’s kind of glorious.

Go read it. Then thank Jules Verne for giving us permission to dream dumb, big, and beyond.

Leia Curie is a fearless scientific journalist who is known for her deeply personal approach to storytelling. Though she follows the tenets of gonzo journalism to a degree, Leia's work is not just about sensationalism or shock value. Instead, she puts herself in the middle of things and delivers work that is as personal as it is informative. Leia is willing to head directly into the fray to get the story by any means necessary, regardless of the political spectrum. Her investigations aren't funded by a major news service or magazine, which allows her obsession with truth and knowledge to drive her work. Leia is an eager detective driven by mysteries with outrageous implications, and she is not afraid of exposing misinformation or conspiracies that promise immortality. With her unique approach to storytelling and her unwavering dedication to uncovering the truth, Leia Curie is a rising star in the world of science journalism.

How a giant cannon, a drunk club, and 1860s optimism shot sci-fi into orbit.