Robot Monster: Cheap, Weird, Iconic

Gorilla Apocalypse and Bubble Machine Doom

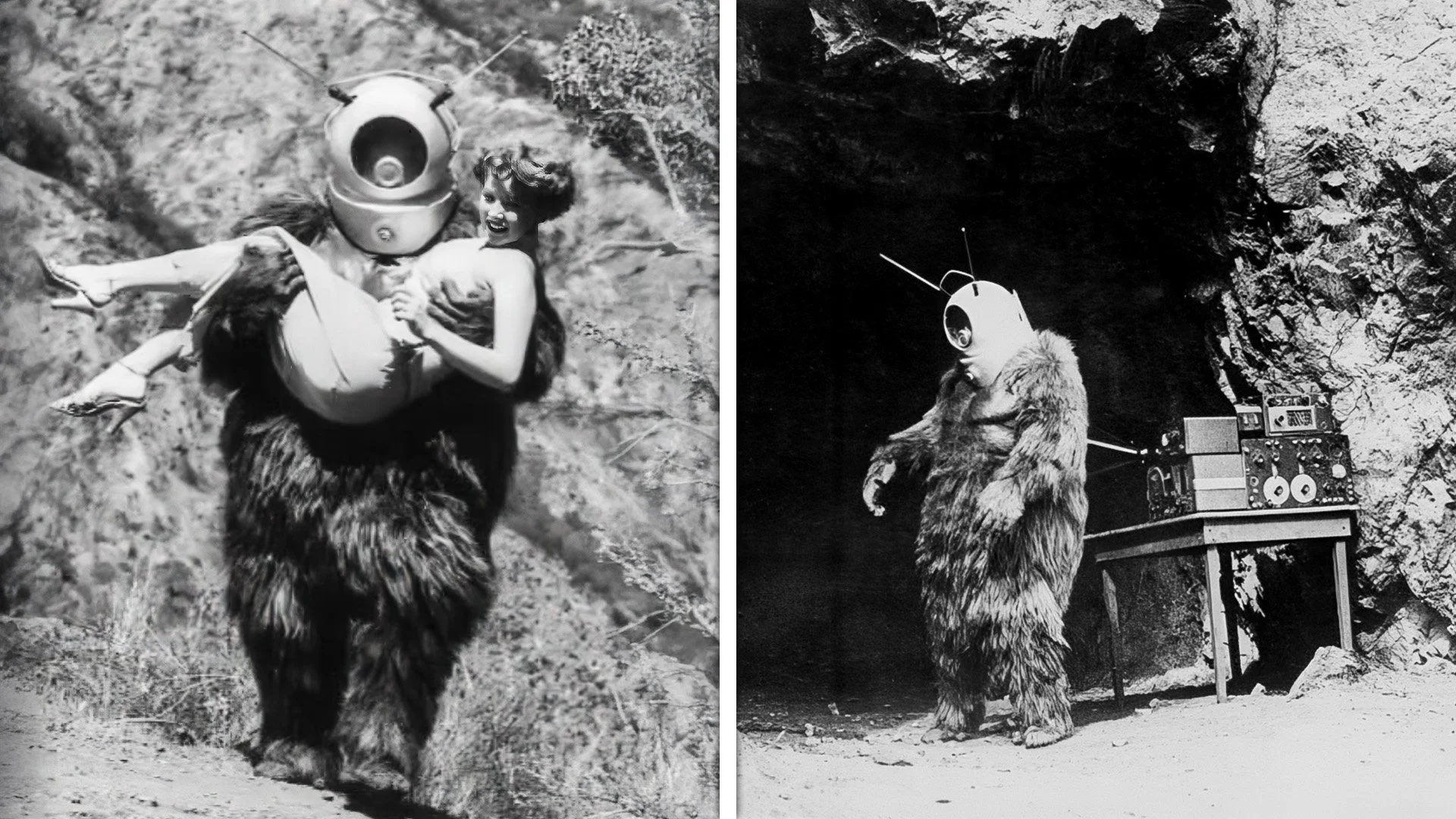

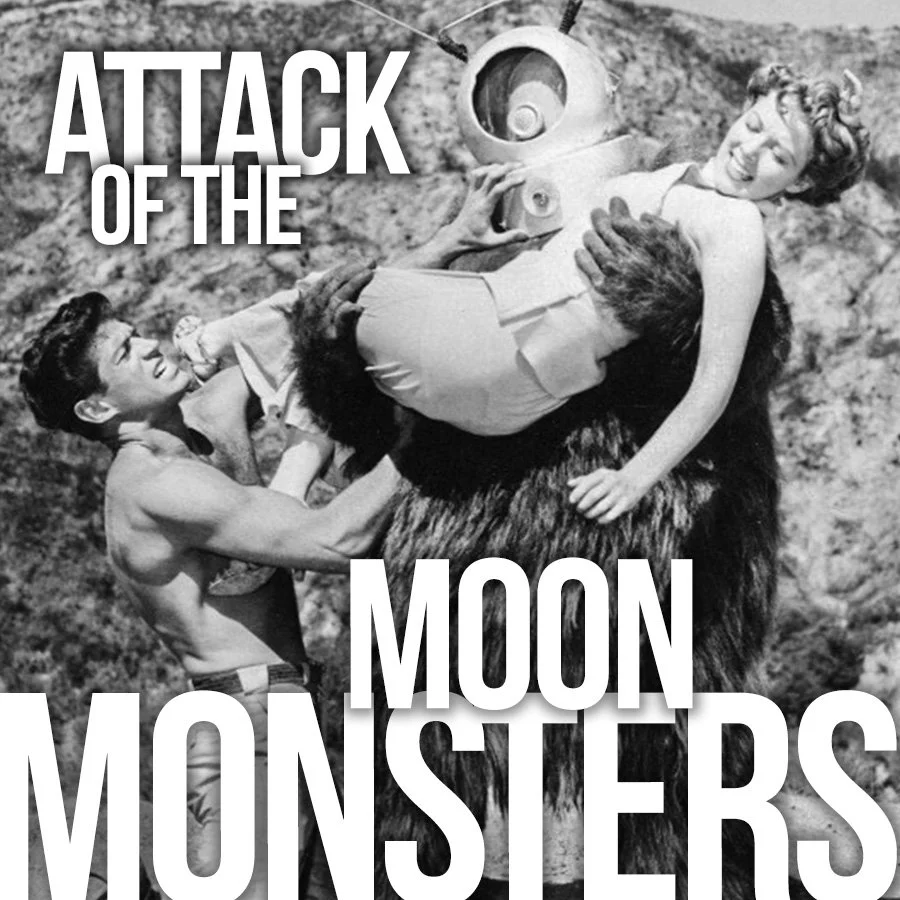

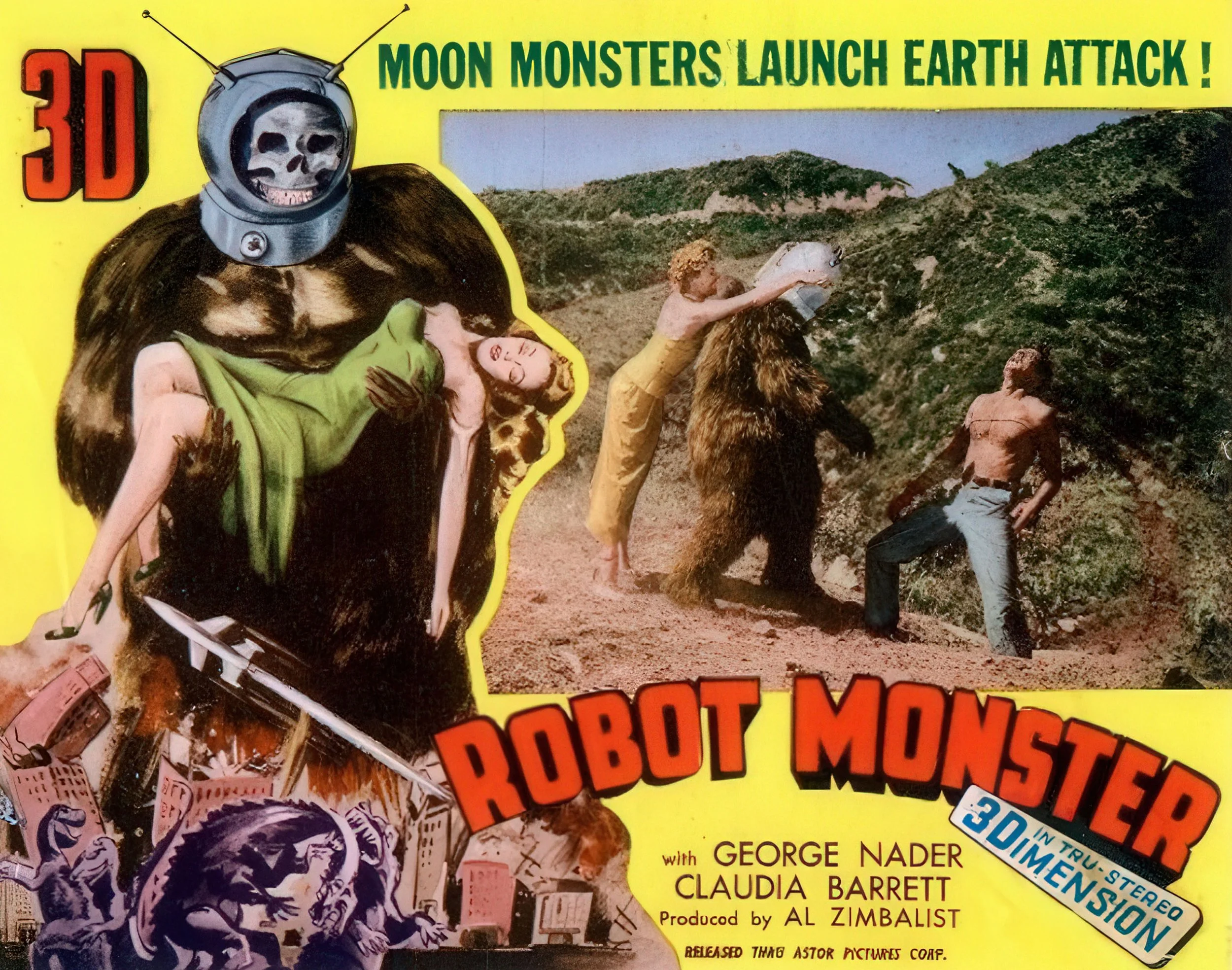

If you’ve ever seen Robot Monster (1953), you probably remember three things: a gorilla suit, a diving-helmet head, and a bubble machine doing very serious “alien communications.” And yeah—people love dunking on it.

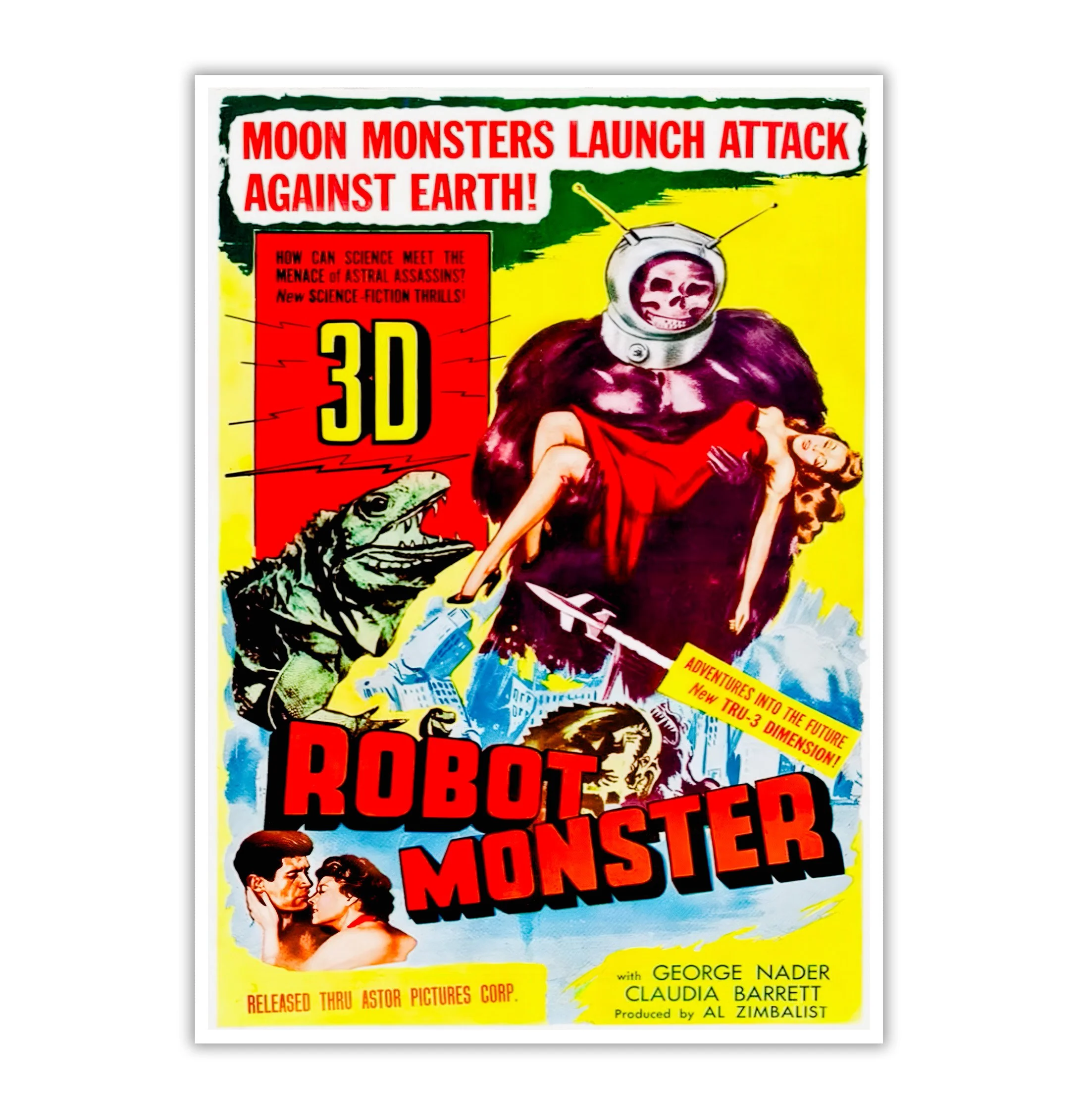

But the real fun isn’t just the roast. It’s the hustle behind it: an indie 3D grab made fast, made cheap, and somehow turned into a legit box-office win. Shot in a handful of days on a tiny budget, it rode the early-1950s 3D craze like a surfboard made of leftover plywood and pure optimism.

And there’s a human story inside the human story: the film’s handsome lead, George Nader, navigated Hollywood’s macho star machine while being a gay man in an era when exposure could crater your career. He wasn’t the kind of actor who played the publicity-game the studios wanted—and later, he even wrote a boldly homoerotic sci-fi novel (Chrome) that reads like a message in a bottle from a closeted age.

-

Robot Monster was a micro-budget 3D swing that still grossed like a champ.

The monster costume is basically “gorilla suit + helmet,” but the 3D photography was the real selling point.

Producer Al Zimbalist was chasing the 3D moment with tech and timing, not prestige. Trailers From Hell

Director Phil Tucker’s post-release story gets dark: a publicized suicide attempt tied to money disputes and fallout.

Star George Nader: peak beefcake image, real-life gay man, and later author of a sci-fi novel that didn’t whisper.

Composer flex: Elmer Bernstein bringing real craft to a movie with a bubble machine.

Robot Monster looks like someone dared a film crew to make a sci-fi epic using whatever was already

in the garage.

A movie that looks like a prank… but plays like a business plan

Let’s get the obvious out of the way: Robot Monster looks like someone dared a film crew to make a sci-fi epic using whatever was already in the garage.

And yet—this thing was engineered to sell tickets. The early ’50s had a full-on 3D craze, and Robot Monster wasn’t trying to be elegant. It was trying to be a “you gotta see this” novelty: a cheap spectacle that would get kids and curious adults into seats. Contemporary reporting and later film documentation consistently frame the 3D as a major hook—sometimes even noting that the 3D itself was surprisingly solid compared to the movie around it.

If you want the truest read on Robot Monster, don’t think “movie,” think carnival attraction—a pop-up haunted house that happens to be on film.

The secret weapon wasn’t the gorilla suit. It was the 3D.

The gorilla suit gets all the memes, but it’s also a clue: this production didn’t have money for a “proper” robot costume, so they used what they could get—reportedly hiring actor George Barrows, who already had a gorilla suit, then adding a helmet and antennas to create Ro-Man.

Meanwhile, the 3D process was the real flex. Producer Al Zimbalist was associated with developing a 3D camera rig for his Tru-Stereo setup—basically positioning the movie as a vehicle for the tech and the moment.

Later restorations and reviews still point out how strong the 3D footage can look when properly presented—like the movie accidentally did one thing genuinely well.

Robot Monster is easy to mock—and it’s fine if you do. It’s practically a rite of passage.

So yes: the monster is funny. But the 3D is the con—and I mean that affectionately, like a magician’s con. “Look over here! Depth! Space! Bubbles!” while the budget sprints away giggling.

The backstory turns weirdly tragic (because Hollywood)

Here’s where it stops being fun.

Accounts of director Phil Tucker’s aftermath are rough: after release, he attempted suicide, with reporting often linking it to disputes over compensation and the film’s profits, plus the career damage that followed. Some summaries even describe him being effectively iced out—like being blocked from seeing his own movie without paying admission.

That’s the part people skip when they label this “the worst movie ever.” Because behind a lot of “so-bad-it’s-good” cinema is the same story: someone tried really hard, the system didn’t care, and the punchline landed on them.

If you want a deeper rabbit hole, there’s a whole “making-of” book specifically about this film’s production story that’s been recommended by genre historians—because the off-screen saga is arguably more fascinating than the on-screen one.

George Nader: beefcake image, real-life risk

Now, about the lead.

George Nader is the classic ’50s “handsome guy the studio wants to package.” The Guardian literally frames him as a he-man beefcake type—and then immediately undercuts that with the reality: in an era when studios pushed gay stars to use “beards” (public girlfriends) as cover, Nader refused to play along in the standard way. He didn’t marry, wasn’t typically seen staging dates with women, and lived with his longtime partner Mark Miller.

Important nuance: “out” in 1953 didn’t mean what it means now. Nader wasn’t doing magazine cover stories about being gay (that would’ve been career suicide). But multiple credible sources describe him as not playing the fake-hetero PR game, and later accounts say his Hollywood stardom was harmed when he was outed.

And then—years later—he writes Chrome (1978), a sci-fi novel about a man falling in love with a male robot, with the “forbidden love” theme turned up loud. That’s not subtle. That’s a signal flare.

So when you watch Robot Monster, yeah, you can giggle at Ro-Man’s helmet… but it’s also worth remembering the lead actor was living in a world where one headline could erase your future.

Elmer Bernstein scored the bubble machine like it mattered

One of my favorite “only in 1953” details: the score is by Elmer Bernstein—yes, that Elmer Bernstein—early in his career, when he was still getting smaller jobs. Sources note he was “greylisted” due to left-wing politics and working lower-budget films at the time, and Robot Monster is one of those odd stepping stones.

Which means this movie contains a hilarious contrast:

visuals: bubble machine

music: legit professional effort

That’s not a mismatch. That’s a tradition. It’s the DNA of B-movies: take the silliest thing imaginable and treat it like it’s the fate of civilization.

“The gorilla suit is the joke. The 3D was the strategy.”

Robot Monster is a little time capsule of 1953: the 3D craze, the indie hustle, the way studios manufactured “manhood,” and the way some people quietly refused to cooperate. It’s a “bad movie” with a surprisingly human aftertaste.

If you’ve seen it: what’s your favorite unintentionally iconic moment—the bubble machine, the helmet, or the deadly seriousness of everyone acting like this is normal?